Taking Action to Resist Racist Systems of Oppression and to Build a Better World for All

by Jessica Xiao

Photo by Penhsamnnang Kan

“I have bodily pain that can’t be treated. An injury to the tailbone. I get anxious if I sit too long.”

“I’m sorry that I’m asking you to tell me about the police violence you experienced,” I said.

“It’s okay — I have to practice telling it in court anyway,” Sherrie-Anne André told me.

In August 2018, Sherrie-Anne André (they/their/them) and three other activists were arrested for protesting outside of Bristol County Jail in neighboring New Bedford, Massachusetts, as part of an ongoing #ShutDownICE Campaign.

I met Sherrie, co-founder of a network called the FANG Collective based in Rhode Island that organizes nonviolent direct action campaigns — and Arely Díaz (she/her), organizer of the ShutDownICE campaign — in November, over a Zoom call (a video conferencing app that knows too much about me now that I work remotely).

They taught me all about the intersections of climate justice, domestic violence, immigrant rights, and prison abolition, and the importance of nonviolent direct actions as one tool to make change.

The main takeaway is: What is worth fighting for, except for a life where our loved ones thrive, not at the expense of other people, but in community with each other and with the Earth?

Sherrie-Anne and their co-defendant Ann were perched on tripod structures, with banners depicting “Abolish ICE Now” and “END Incarceration & Deportation. STOP Family Separation. AHORA!” Two others locked themselves to a cement-filled tire with the words “Abolish ICE” at another entrance.

Source: Fang Collective Facebook page

“The police pulled all the legs of the tripod out. The middle slammed [Ann] down, and they dropped the poles on her body — just witnessing that is violence in itself, because now I know they’re going to do it to me. They had already been threatening to kill us — ‘if you hurt us, we will hurt you.’ They were mad at us for being in the way.”

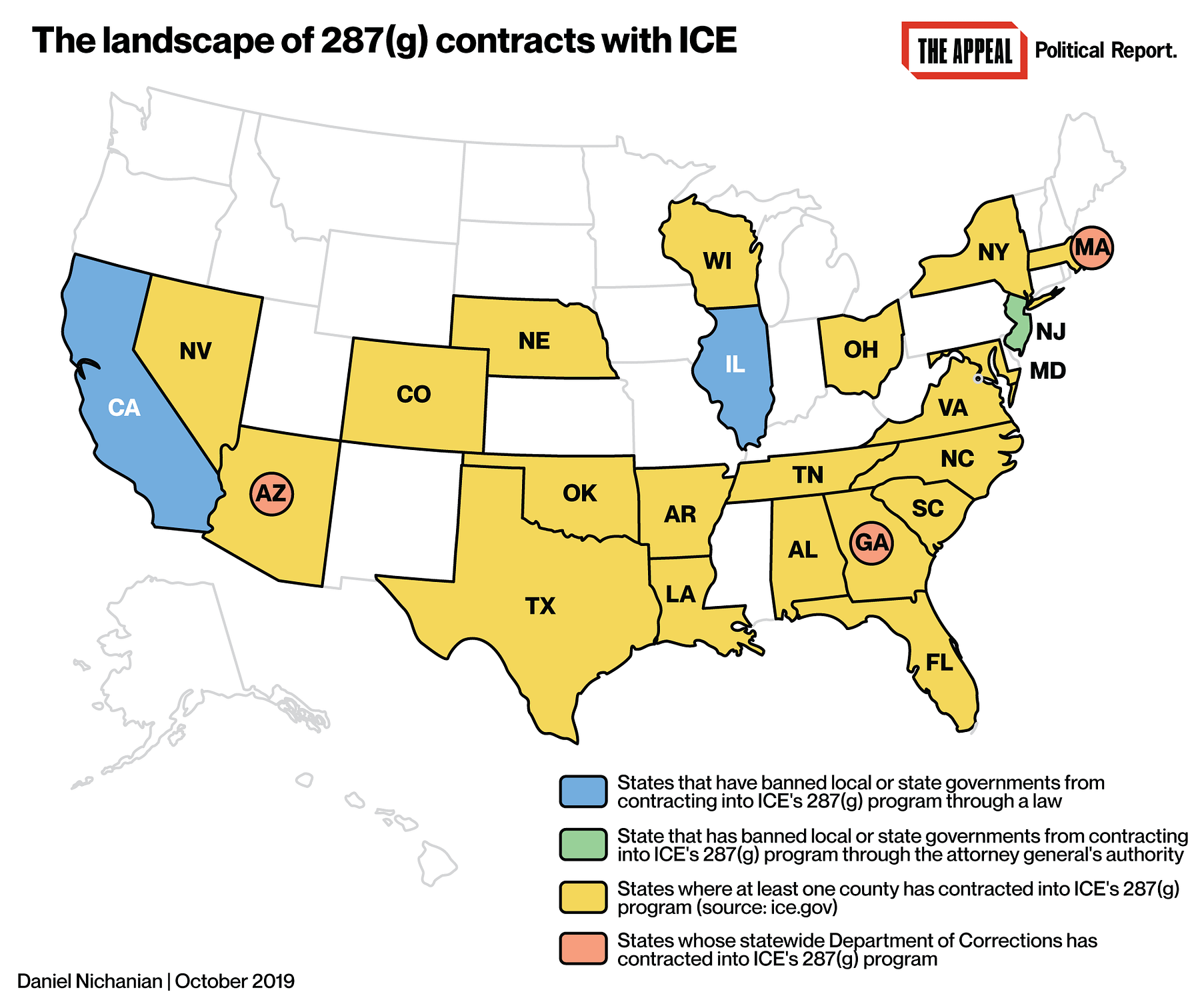

Their action in August (described above) was in protest of IGSAs and 287(g) agreements: Bristol County Jail has an intergovernmental service agreement (IGSA) that allows the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Agency (ICE) to pay for the use of the Bristol County Jail to lock up undocumented immigrants.

Source: The Appeal

Bristol County Jail also has a 287(g) agreement with ICE that allows police officers to act with the authority of immigration officers. Local officers go through a woefully inadequate four-week training (ICE officers themselves must complete a 12 to 16 week training) and are given authority to enforce immigration law. (Read more about these agreements here.)

Who AGREED to these agreements, though? A man named Thomas Hodgson, sheriff of Bristol County, BFFs with Trump, and staunch supporter of a border wall between the U.S. and Mexico, offering to send Bristol County jail inmates to help build the wall.

He once said, “The ink of no other project that would have such a positive impact on our inmates and our country than building this wall.”

Although Massachusetts, described in broad strokes, is a blue state whose residents vote Democrat, Hodgson is representative of too much of this nation, where backward and racist ideas about the incarcerated and immigrants flourish and are rarely pushed back against institutionally (regardless of geographical location).

He has been sheriff of Bristol County since 1997, and in his most recent election, he ran unopposed, a reminder of why it is important to give some attention to local elections (and to participate in local government), if you have the capacity — and why it is important for local governments to make it easy for community members to participate.

Sheriffs have a significant amount of power today. They run law enforcement at the county level with little accountability. Hodgson had unilateral decision-making power when it came to collaborating with ICE and he did not have to seek approval or face accountability from his constituents.

I was locked into a piece of equipment when they pulled out the poles of the tripod. I didn’t hit my head on the ground as hard as she did. I landed on my tailbone on the pavement. They tried to use pain compliance* on me, punching me in the nose over and over again with their fists, rolling my ears, pulling my arms, to get me to unlock myself.

Men came over me with knives and cut my gear off of me while I was on the ground. They pulled me to the side to remove the lockbox(?) because I didn’t unlock myself through their use of pain compliance, and then dragged me to be arrested.

Having worked with incarcerated and justice-involved young people mostly from Washington, DC, before joining the Climate Justice Alliance, I was grateful for Sherrie’s actions because I had witnessed firsthand how the U.S. prison system is an ever-spreading stain that perpetuates the legacy of how this country came to be: on the blood of those considered other — and still treated as other to this day.

Undocumented immigrants shouldn’t be detained for changing where they live on the planet. And people who have been found guilty (rightly and far too many times wrongly so) of breaking the law shouldn’t be thrown away, behind bars, to live in inhumane and often life-threatening conditions.

I mention my experience because I didn’t grow up in an overpoliced community and was not negatively targeted by the police. I didn’t grow up knowing anyone who’d been arrested or locked up. So I learned what I know today through friends sharing their experiences with me, through reading lots of letters from incarcerated folks, from reading the research of investigative journalists, researchers, and more.

I see that we can grow up with such different experiences of law enforcement and the government based on our unique sets of identities and circumstances. It can be easy to underestimate or dismiss the devastating consequences on the psyche and wellbeing of entire communities from racial profiling, police shootings, and extended interactions with the criminal justice system when your own relationship with law enforcement and the government has felt trustworthy, or distant at worst.

And I can rant about how unjust, racist, and classist the criminal justice system is and how sh*tty prisons are for hours — in fact, I did, while drafting this — so thank my colleagues for cutting out most of it. But the point is, just as with our modern police force which originated from slave patrols and night watches to catch those who escaped from slavery, ICE is built on the same racist, classist, and punitive foundations as the criminal justice system.

Because to be honest, the idea “If you didn’t do anything wrong, you have nothing to fear” is a privilege.

After we were arrested, we were seen by a doctor for a second. He glanced at us, said we look fine, and left. We didn’t receive any medical treatment.

Then we were held in Ash Jail. They play this video about prison r*pe over and over again, and have you sign a form to say you’ve gone through sexual assault training, when it just warns you not to interact with people, don’t share food. It was a f*cked video. To have a concussion and sit through all that.

Jails and prisons are designed in a way that fosters dehumanizing interactions — and they can often get away with lots of human rights abuses beyond restricting freedom (like not evacuating a prison during a climate disaster) and constitutional violations (like banning books or decades of solitary confinement). Justifications abound to cut costs and make more profit just because people aren’t paying close attention or subconsciously believe it’s okay to treat people convicted of a crime in a punitive way. (Let’s not forget, wardens have a lot of leeway over deciding how to run their facility and can justify taking away rights by invoking concerns about “safety.” ?)

By the way, Bristol County Jail has one of the highest suicide rates in all of Massachusetts, a pretty damning reflection of Hodgson’s lack of empathy.

It’s harder for me to be steadfast about my ideals that no one should be locked up in inhumane conditions or lose all of their freedom forever when I think of someone like Harvey Weinstein or Larry Nassar who have caused so much harm, but I still think the prison system as it exists today needs to be abolished and we need to reckon with how do we create a just justice system that doesn’t disproportionately criminalize particular communities like poor people, people with substance abuse issues or mental illness, and Black and Brown folks?

Knowing that incarcerated citizens are already subject to cruel conditions, just imagine being detained without even the supposed rights of U.S. citizenship.

In fact, we don’t have to imagine — ICE detainees at the Bristol County Jail wrote a letter to the public about their conditions in 2018:

“What we need in here is the support from people and organizations on the outside to help us raise our voices to denounce the system. We’ve been kidnapped.…There’s one toenail clipper per one hundred who live here. Nothing is sanitized. We are not entitled to extra clothes, things that are supposed to be there for no cost are being sold in the commissary. The items are so expensive that we can’t even buy them.…We cannot truly complain because we are immigrants. We do not have any rights in this country — that’s what we are told.”

In July 2018, the people imprisoned at Bristol County Jail, in solidarity with the people detained, joined together in a hunger strike protesting these conditions. Sherrie’s direct action was in solidarity with this strike.

As a low-income Indigenous person [of Puerto Rican and Southeast Asian descent], my body is the only social capital I have — I don’t have money to file a lawsuit against energy companies. I don’t live in Massachusetts where these detained immigrants from Rhode Island are being held and I can’t vote there. I have to do something — how would I do an action as a person of color with access to safety supports and elements of healing?

Of the four activists arrested for protesting outside the jail, three of the defendants took pleas: two of them served a ten-day jail sentence. The third codefendant paid $3,000 in restitution.

When I spoke with Sherrie, they were preparing to fight two charges in court: a trespassing charge that carries a sentence of 30 days in jail and a disturbing the peace charge of a $150 fine. And this is just another example of the fickle and inconsistent application of law in order to enforce particular states of societal obedience.

With a trial date in January, Sherrie, their lawyers, and their team of friends and organizers were all planning their strategy in court as well as how to use the trial to publicize and raise opposition to Sheriff Tom Hodgson, as well as opposition to collaborations between local law enforcement agencies and ICE more generally.

“FANG believes in long-term jail and court support,” Sherrie told me. What we need is “For emotional support, some people experience depression from action or police violence, to support accessing resources like dental work because dental healthcare is notoriously lacking in jails and prisons, to check in on family and help them understand what is going on, to strategize, to pay small fines for community members. I am privileged to have this much support going through the process.”

It’s taken me seven years to find a therapist I can talk to about [direct] actions. As a mixed status queer Indigenous / South Asian woman, it’s f*ucking hard to find a therapist to talk to about cultural things because they don’t understand. ‘Why does your mom do that?’

And then you have to figure out, are they a police apologist? Are they going to tell me or my loved ones it’s our fault when we’re abused or violated by the police?

In January, my colleague Senowa travelled to Massachusetts to attend the trial in support of Sherrie, and a series of events around the trial (a community dinner and a march to Ash Street Jail), but the trial was postponed, and court supporters were aggressively removed from the courthouse without warning.

“The judge cited ‘court congestion’ as the reason for it being postponed,” Senowa emailed me, “Pretty sure that was BS — but about 100 people showed up to court to support, and brought snacks, coffee, and cigarettes to hand out to folks who had court dates.”

Finally, the trial took place over three days just last week, and Senowa graciously sent me her notes from the trial, the most egregious tidbits here:

- lots of potential jurors had ties to cops/were retired cops which is apparently very indicative of Bristol county

- prosecution actually opposed using gender neutral language for Sherrie, and when pressed why said “I don’t know”

- prosecution argued that because Sherrie was able to walk away from the fall that they were fine, which was then contradicted because they also said that they had to pick sherrie up off of the ground

- officers were caught on video saying they didn’t care if the activists were hurt

- Sherrie was not even allowed to mention Sheriff Hodgson’s name — it was his court.

- Sherrie had safety gear on to protect them in the tripod, the officers cut that first, which could have been extremely dangerous

On March 9, Sherrie was found guilty and sentenced to 30 days in jail.

And speaking of direct actions, young, white college students are celebrated and supported.

The community reception towards bodies like mine or Black folks doing this work — we are not celebrated or heroes. We don’t do this work to become one — but our stories become hidden and fresh movement folks move in starting from scratch without ever checking to see how issues have impacted communities of color and how we’ve been resisting the whole way. Our community organizing gets erased and white people just assume we haven’t done anything.

FANG, which at its founding stood for “Fighting Against Natural Gas Collective,” started six years ago to fight fracking because of violence against women.

Yes. That is not a typo. Sherrie had been working in domestic violence shelters on the East Coast — which were isolating and impersonal spaces that were un-inclusive of trans women and often replicated the dynamics of an abusive relationship: “The food in the shelter has been locked up and people would have to get permission to access food. Some shelters only let one family cook at a time or wouldn’t let women watch each other’s kids because it’s a “liability,” so it’s difficult for people to bond because they can’t build trust with each other. And how are you supposed to get to your job interview without public transportation if you don’t want to bring a young child on a bus for so many hours?

They then moved on to a domestic violence shelter in South Dakota on an Indigenous reservation, a much more healing space: “There were opportunities for people to share food and cook together. Social services under capitalism want healing to be your personal responsibility even if it’s not ‘your fault’ to get here to begin with. Shelters are not fun — but why does it have to be this awful space for people?”

While there, the Midwest experienced massive flooding. At the same time, man camps — miles of trailers — were being set up in the area in preparation to build the Keystone XL pipeline.

Sexual violence has been demonstrated to increase after natural disasters, with Indigenous women being one of the most vulnerable populations because abusers can get away with it (it is difficult to prosecute a U.S. citizen after they’ve left the reservation because of jurisdictional issues).

Altogether, this set of conditions significantly constrains the ways in which Indigenous women can live and move through the world — and it was taxing the shelter. The challenge became, how to access more funding to run the shelter with more beds? There was nowhere for people to go.

It was becoming clearer and clearer that the consumptive way we treat the Earth is the same consumptive way patriarchy teaches men to treat women — capitalism and patriarchy and white supremacy intertwine at great cost to all of us across the United States — and at greater cost to those who are seen as commodified or disposable. Thus, gender justice must include climate justice, and climate justice must include gender justice.

That was the catalyst for Sherrie to start connecting with anti-fracking campaigns, moving back to the East Coast and figuring out how they could uplift and support the work of organizers from Pennsylvania through Florida.

I’m afraid of what it would look like to have children — to want children and family. My partner and I talk about it, but we’d have to stop organizing in order for that to happen and that also seems not fair.

Fighting Against Natural Gas or FANG started as a support network and a way to share resources, Sherrie told me. It is mostly capacity building work — for folks to share with each other information about writing grants, about seeking funding, about how to start doing their own work, to receive trainings on non-violent direct actions, or to seek connections with others doing similar work.

It expanded to include campaigns targeting the military’s largest supplier of cluster bombs — Textron — which is based in Rhode Island.

Then in 2016, they changed their name to the FANG Collective, as they adapted to the organizing needs of its members — children of immigrants, undocumented, and mixed status folks — and helped to form a coalition of people and grassroots organizations called AMOR: Alianza para Movilizar Nuestra Resistencia (loosely translated: AMOR: Alliance to Mobilize Our Resistance), which shepherds the #ShutDownICE Campaign, the natural next step.

And direct action is not invented for you to talk and use them without a sense of urgency. [Direct actions] were used in crisis — and it is crisis. It is hard to teach folks of privilege that. They think it is a game sometimes. They feel like they’re supposed to do something, but then they don’t.

And when they do, they want all the resources they have access to — like media, therapy, yoga, etc. — none of those resources are offered to us. Requiring lots of resources to heal is sloppy, and extracts a lot of resources.

We can’t afford to mess up. We don’t have the money to f*ck it up. They also don’t have a level of fear of the police. I’m very aware of how the police can harm me and other people, particularly Black folks, in my organization, and I have to think, how am I going to protect every single one of you so you can participate in the ways you want to?

It is definitely a challenge to keep track of the many coalitions, and it quickly can become a confusing web that’s hard for newcomers to understand fully without time, but it also shows how intentional FANG is about working in ways that are inclusive, equitable, and democratic, grounded in the Jemez Principles for Democratic Organization and Principles of Environmental Justice (both established about two decades ago and tenets of the climate justice movement).

Similarly, it is difficult to keep track of how varying oppressions are connected to each other.

Why is it important, as we figure out how to stop contributing to climate change and how to adapt to climate change, to also figure out how to abolish ICE or dismantle racist institutions or fight extractive practices that prioritize profits over people or how to live with each other with more kindness, care, and thoughtfulness?

The key is, they all work together to support this broken system and the status quo.

And in all honesty, even FANG sometimes isn’t sure how they fit into the Climate Justice Alliance. That’s the beautiful challenge of building a future that doesn’t exist yet — we can feel it and we can work towards it, but it evolves in unexpected ways as we do the work of figuring out how to live our values of prioritizing each other and prioritizing justice even when we have conflicts or ambiguity or differences in values and tactics.

Why is it important to make sure that transitioning away from fossil fuels is actually much more than that? That we’re fundamentally changing our societies and economies to be more just and to take care of one another, and to ensure as we transition we stop the historical harm that these industrial and capitalist systems have inflicted on our communities for centuries?

Because if we don’t, we’ll continue to cause harm to each other and we’ll continue to behave in ways that actually created the climate crisis in the first place.

That’s why Just Transition is important.

There are links that are more obvious on paper as well: as climate disasters increasingly displace people, there will be more climate refugees, but both Sherrie and Lee caution against this justification for centering social justice in climate change work.

“I don’t give a f*ck why someone is here — they shouldn’t be detained. We need to be mindful in environmental movement to not create a good/bad immigrant narrative,” Sherrie said.

Besides, we should be more expansive about our language, when it comes to climate, says Lee, “There are obviously direct links between people’s countries and climate — the climate of where and when you’re living. What is the climate we are trying to survive? And that’s what Just Transition needs to be. Things don’t fit neatly into a box and we don’t have to try so hard to find the connections — they just exist. We know they exist. We use the language we know to talk about them as they exist. We recognize the interconnections and encompass the interconnections without us having to spell it out all the time.”

If you’re looking for NVDA training, pay attention to who is doing the work. If a group or organization or a few people are doing work I really value and want to participate in, I approach humbly and ask how I can support that work.

Oftentimes, direct action trainings are not for people to do them, but for them to understand the parts and history of direct action, and within our own communities. Not asking to come learn a tool to apply, but to understand why it exists. That’s how we [FANG] approach direct action. It’s a way of us teaching people a history class. You may or may not use it, but at the least understand why people are doing it. This makes it safer for people who choose to do it.

I spent a year and a half painting banners before I ever asked to participate in anything. If you want to hop onto a direct action campaign, you might be asked to do support roles before risk roles because they want to understand you enough to be able to support you afterwards. Who are the people who are supposed to take care of me after I take? this risk? It’s scary to think about breaking the law — it’s a mindshift that you do need a lot of support going into.

Recently, a friend of mine has used the expression “building the car while driving it” and that’s what the Climate Justice Alliance is doing as it supports Just Transition work — we have to build the world we want to see while acting like we are already living in it.

The Climate Justice Alliance has six meta-strategies. One of which is fighting the bad. I like to think of what FANG does as the first one, even though we need to do everything concurrently — and preferably using the same outlook — can we build a strong, lasting, sustainable, and healthy NEW way of being with the same tactics we use to fight the bad? I’m not sure. It’s not always realistic. But what many involved in this work, like FANG, are currently doing certainly points that it is possible.

Ensuring that our communities have rights — that’s fighting the bad

Ensuring our communities receive social justice is fighting the bad.

All of these pieces are necessary for a Just Transition to an economic and social system that prioritizes the wellbeing of humans, community, and Mother Earth.

I started in nonprofits and lobbying. We would work really hard to have a new person in office, then our budgets would be cut and we’d have this cycle of having the next elected official fixing our problems. But resistance can look and feel different.

Direct action is seemingly inaccessible because it feels uncomfortable to use our bodies — but we have to feel uncomfortable. It is a visual representation of how we are feeling, and we don’t have to be the most verbally eloquent to be heard. If we have to be polite and respectable, we are subjecting ourselves to white supremacy by using “the right ways” to request change and we cannot wait — we cannot keep waiting.

The moral of the story? Climate justice is about so much more than the “climate.” The mainstream’s definition of climate just won’t cut it. Climate actually speaks to our entire environment (not a narrow vision that only relates to weather conditions) but rather, the interlinking set of conditions that we experience every day. As FANG demonstrates, frontline communities are leading the way in addressing the multiple factors that continue this cycle of devastation and destruction in our communities, including climate change.

It is through this lens that we come to climate justice and understand the importance of working not just for a transition away from fossil fuels but for a Just Transition so that our communities not only survive, but thrive.

If you want to support the FANG Collective, donate to support the costs of Sherrie’s trial, learn more about the #ShutDownIce Campaign. or visit their Facebook page to learn more about other things you can do.